In the world of sous vide cooking, eggs hold a special place. They are a perfect canvas for exploring the nuances of temperature and time, two variables that a sous vide immersion circulator controls with unparalleled precision. Among the various experiments, comparing the yolk texture of an egg cooked at 63°C versus one cooked at 68°C is a classic demonstration. The difference is not merely a matter of a few degrees on a dial; it is the difference between a silky, custard-like dream and a firm, crumbly classic. This exploration delves into the science and sensory experience behind these two distinct yolk states.

The journey of an egg yolk during sous vide cooking is a story of protein denaturation and fat emulsification. An egg yolk is a complex mixture of proteins, fats, water, and emulsifiers like lecithin. Each of these components reacts to heat in a specific way and at a specific temperature. The magic of sous vide is that we can hold the entire egg at an exact temperature, allowing these reactions to proceed uniformly throughout, something nearly impossible to achieve with traditional boiling or poaching. At 63°C, we are gently coaxing the proteins to unwind and bond, while at 68°C, we are applying a more assertive command for them to set.

Let's first immerse ourselves in the world of the 63°C sous vide egg. This temperature sits just at the threshold where the major yolk proteins, livetins and phosvitin, begin to denature. The process is slow and gentle. The result, after about 45 to 60 minutes, is a yolk that is utterly transformed. It is thick, incredibly creamy, and boasts a luxurious, velvety texture that is often described as custard-like or even gelatinous. It holds its shape when the shell is cracked open, but it will ooze slowly, like a thick lava. The color is a deep, vibrant orange or yellow, depending on the hen's diet, and it appears almost glossy.

The mouthfeel of a 63°C yolk is its most remarkable feature. It is smooth and rich, coating the palate without any graininess. It lacks the dry, powdery quality that can sometimes be found in fully set hard-boiled yolks. The flavor is profoundly eggy and concentrated, as the gentle heat preserves more of the volatile aromatic compounds that can be driven off by higher temperatures. This yolk is a star component. It is perfect for topping avocado toast, where its creaminess creates a sauce-like effect, or for crowning a bowl of steaming ramen, where it slowly mingles with the broth to enrich it. It can be carefully placed on a salad or used as a decadent dip for soldiers of toast.

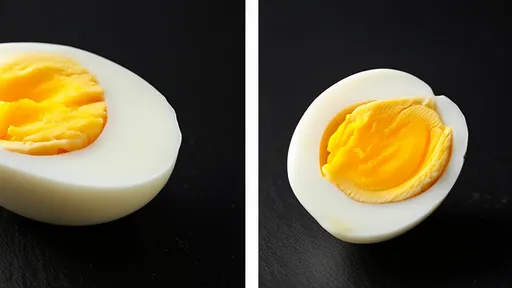

Now, we turn up the heat to 68°C. This five-degree jump represents a significant increase in thermal energy, pushing the yolk proteins well past their denaturation points and encouraging them to form a much tighter, more extensive network. The yolk at this temperature undergoes a more complete setting process. After a similar cook time, the result is a yolk that is firm yet still tender. It is completely set, but it retains a remarkable moistness and a soft, almost fudgy consistency. It is not crumbly or chalky like an overcooked hard-boiled egg can be. Instead, it slices cleanly and holds its shape perfectly.

The texture of a 68°C yolk is best described as firm and moist, reminiscent of a perfectly hard-boiled egg but with a superior, more uniform consistency from edge to center. There is no green-grey ring of overcooked sulfur compounds around the perimeter because the temperature was never high enough to produce them. The flavor is still rich and eggy, though some connoisseurs argue it is slightly less complex than its 63°C counterpart due to the slightly higher heat. This yolk is incredibly versatile for applications where a runny yolk would be a mess. It is ideal for slicing onto salads or grain bowls, chopping into egg salad (where it won't make the dish watery), or simply enjoying as a handy, protein-packed snack. It provides the familiar satisfaction of a hard-boiled egg but with a noticeably more pleasant and refined texture.

The choice between these two temperatures is not a matter of right or wrong; it is a matter of purpose and preference. It is the difference between a sauce and a slice. The 63°C egg is an act of culinary luxury. It is about creating a specific, decadent experience where the yolk itself is a transformative sauce or a rich garnish. It requires a bit more care in handling and is best enjoyed immediately. The 68°C egg, on the other hand, is about utility and a perfected classic texture. It offers the convenience of a firm yolk that can be used in a wider range of prepared foods, stored, and sliced without issue. It is the choice for meal prepping or for dishes where structural integrity is key.

Ultimately, this five-degree window, from 63°C to 68°C, beautifully encapsulates the power of precision cooking. It shows that minute changes in energy input can lead to dramatically different outcomes in something as simple as an egg. For the home cook or the professional chef, understanding this spectrum allows for unparalleled control over the final dish. It turns the humble egg from a single-ingredient food into a variable component that can be tailored to elevate any recipe. The next time you lower an egg into a water bath, remember that you are not just cooking; you are conducting a delicate symphony of proteins, and you are the maestro, with the immersion circulator as your baton.

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025

By /Aug 20, 2025